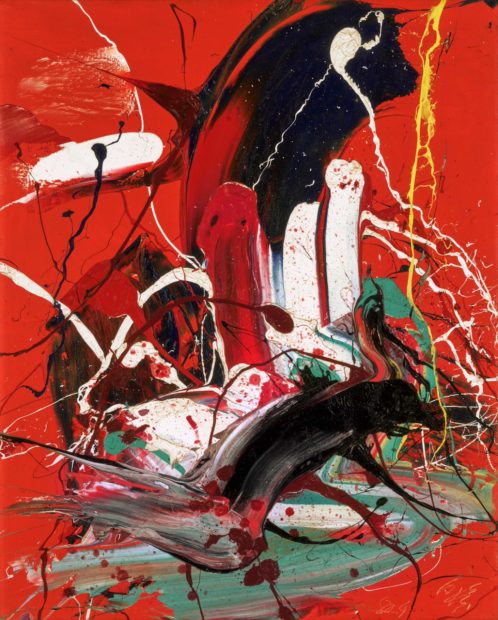

白髪一雄「妙咒」〜密教シリーズ〜

白髪一雄「妙咒」〜密教シリーズ〜

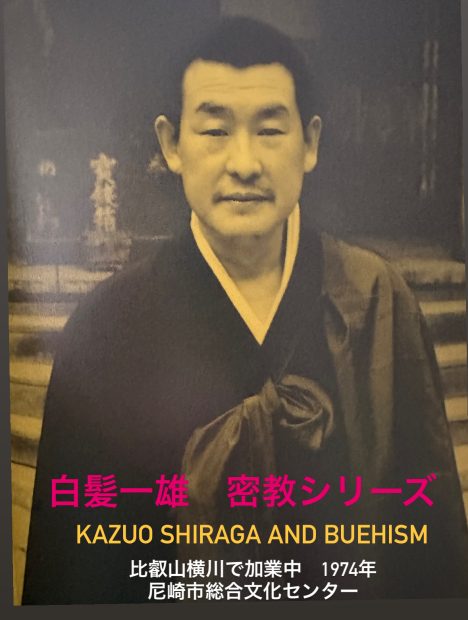

白髪一雄は猪狩の途中で梵字の卒塔婆に出会ったのが縁で密教に興味を深めて’70年代の比叡山に入山修行して得度しました。そのごの〜密教シリーズ〜の一点です。

「咒(じゅ)」とは、サンスクリット語の「マントラ(真言)」を意味し、「妙咒」は「すぐれた真言」あるいは「神秘的な力を宿す言葉」と訳されます。

仏教、とりわけ『法華経』や密教の経典において、「妙咒」は衆生を救済する力をもつ呪文として登場します。

この“魂を動かすことば”、“秘められた力を宿す美のことば”ーそれこそが芸術と通じるものであり、タイトルに深い意味を託す白髪にとって、《妙咒》はまさに渾身の表現であり、白髪一雄にとって絵画そのものであったとも言えるでしょう。

精神と肉体を捧げた祈りの痕跡 ではないでしょうか?

Kazuo Shiraga “Myōju” – From the Esoteric Buddhism Series

Kazuo Shiraga’s interest in Esoteric Buddhism deepened after he encountered a stupa inscribed with Sanskrit characters during a boar hunt. In the 1970s, he entered Mount Hiei for ascetic training and was ordained.

This work is one from his subsequent Esoteric Buddhism Series.

The character “咒 (ju)” comes from the Sanskrit word mantra, meaning a sacred incantation. “妙咒 (Myōju)” can be translated as “sublime mantra” or “a word imbued with mysterious power.”

In Buddhism—particularly in the Lotus Sutra and Esoteric scriptures—“myōju” appears as a sacred formula believed to have the power to save all sentient beings.

These “soul-stirring words,” these “hidden words of beauty and power,” are deeply connected to the very nature of art.

For Shiraga, who gave profound meaning to his titles, Myōju can be seen as a fully realized expression—painting itself as mantra.

Might this not be the trace of a prayer offered through both spirit and body?