足の筆で描く東洋のスピリット・白髪一雄 Kazuo Shiraga—the spirit of the East, painting with his feet as a brush

久し振りに尼崎文化センターの白髪一雄記念室に行った。今の展示は〜密教との出会い〜、「大威徳尊」 1973がメインに展示されていた。私は入るなり撃れてしまった!本当に腰が抜ける思いがした。まるで足萎えのようにただ立ち尽くしていた。生前お出会いした穏やかな白髪さんについつい惑わされて身近な存在に思っていたが、それはとんでもないことであったのだ。白髪師の本体は遥か天上界に在ったのだ。

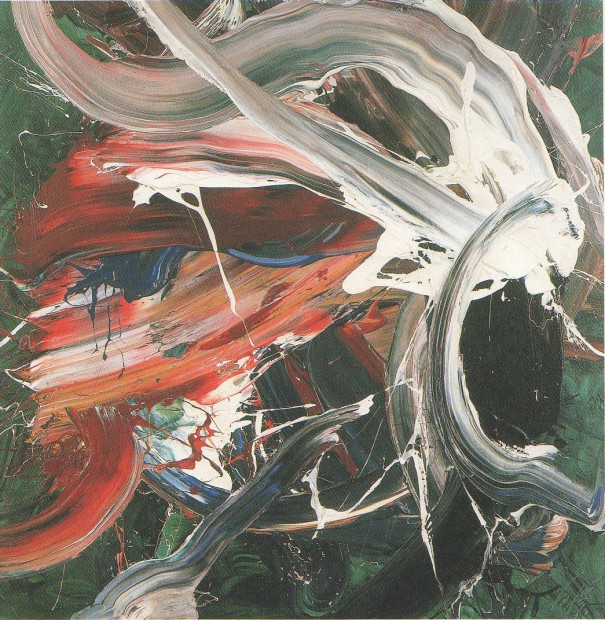

I recently went to see the Kazuo Shiraga room at the Amagasaki Cultural Center, my first visit in quite a while. The current display, entitled Mikkyo to no Deai (encounter with esoteric Buddhism), featured Daiitokuson (1973) as the main exhibit. As soon as I saw it, I was stunned. I just stood there, unable to move. The calm and peaceful Kazuo Shiraga that I had met had lulled me into a sense of familiarity, thinking that I knew him, but this painting unceremoniously shocked me into realizing my error, demonstrating that Shiraga’s essence was actually on a completely different level, out of this world.

書や墨彩に精通していた白髪師は足を、足指をまるで筆のようにしで描いたのだ。作品から親指の小指の微妙な感触が生々しく伝わってくるのを感じる。ロープの勢いと足指の刹那の痕跡が作品となる。なんとその繊細なことだろうか?私は今までなんと大雑把な見方をしていたことだろうかと恥いった。足指をこれほど芸術に昇華した人はいない。改めて足で描くパイオニヤであることを認識させられた。

Shiraga was very familiar with calligraphy and bokusai-ga (sumi ink paintings that incorporate color), and used his toes to produce what seemed like exquisite brushwork. This work vividly communicates the delicate touch of his big and little toes. The momentum of the rope and the momentary traces left by his toes combine perfectly. The delicacy is astounding. I’m ashamed to admit that until now my perspective had been too crude to notice. Surely no-one else has ever incorporated every fiber of his toes into his art to such an extent. Shiraga is indisputably a true pioneer of painting with the feet.

作品から放出される猛烈なエネルギーのエスプリ、それは西洋的なものとは違う。私たちの DNAの奥底に潜む大陸的な東洋のエスプリを触発する。 そして長澤蘆雪、曾我蕭白、富岡鉄斎の作品を目にした時と同種の感性を発掘させられる。学芸員さんから白髪師は富岡鉄斎に憧憬していたと聞く、合点!

The esprit behind the ferocious energy emitted by this work is not the same as western esprit. It triggers the eastern, continental-Asian esprit that is deeply embedded in Japanese DNA. You can discover a similar aesthetic sensibility when you encounter a work by Nagasawa Rosetsu, Soga Shohaku, or Tomioka Tessai. When the curator told me that Shiraga was a fan of Tomioka Tessai, I wanted to shout, “Yes!”