中辻悦子展

悦子さんの底が抜けた!と会場に入るなり感じました。そして、このおおらかな生命力のパワーに圧倒されました。<元永定正>という強烈な磁力から解放された裸の中辻悦子が在る、と思いました。この伸びやかさと洗練されたシンプルさは元永さんの作品さえうじうじしているように思えてくるのです。作品と対峙していると、会場に来る時に大阪駅の路上で演奏していた南米の Vivandes と重なり、私の魂は無限に解放されていくのでした。この展覧会は神戸・元町のギャラリーヤマキで 5/6 まで開催しています。

悦子さんの底が抜けた!と会場に入るなり感じました。そして、このおおらかな生命力のパワーに圧倒されました。<元永定正>という強烈な磁力から解放された裸の中辻悦子が在る、と思いました。この伸びやかさと洗練されたシンプルさは元永さんの作品さえうじうじしているように思えてくるのです。作品と対峙していると、会場に来る時に大阪駅の路上で演奏していた南米の Vivandes と重なり、私の魂は無限に解放されていくのでした。この展覧会は神戸・元町のギャラリーヤマキで 5/6 まで開催しています。

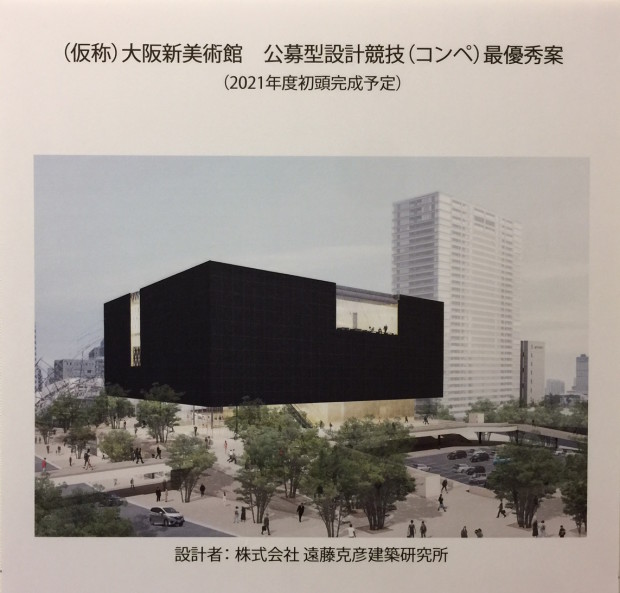

昨日、江之子島文化センターで大阪新美術館準備室の「具体美術協会関係資料」の報告会 に行った。最近、遺族から ダンボール 220箱分の資料が寄贈された。芦屋美術博物館や大阪大学にあったものも一括され大阪新美術館準備室が gutai の拠点となる。資料は宝の山ではあるがこれほどの膨大な資料を活用できるようにするには膨大な時間とお金が必要であろう。しかし程遠い現実の条件の中での学芸員さんの作業に脱帽する。半世紀以上経たフィルムの修復は気の遠くなるような作業があったと思う。新たに修復できたのを入れて16 本のフィルムが上映された。私は凝視した。途切れたり雨が降る荒い映像をイメージで修正しながら。高解度の映像が溢れている今見ても、それらの映像から飛沫が降りかかってくるのに gutai を改めて識った思いにさせられた。

特にラストの<具体美術まつり WXPO’70 お祭り広場における人間と物体のドラマ>は素晴らしい!毛糸人間(毛糸で編んだドレスの女性がスカートの端からくるくる舞いながら解かれていく)、ラメ人間(ラメに包まれた数人が踊る、万華鏡のように変化しながら)、赤人間(白髪一雄の三番叟の団体の踊りはど迫力あり)、ロボットの犬(小屋から無数の子犬のロボットが舞台いっぱいに歩き出す、女の子と坊やが倒れた犬の救助に走り回る)、プラスチックカー(ヨシダミノルのプラステックカーが光を放ちながら走り回る、大きなプラステックの塔のまわりを)、ふくらむ(吉田稔郎の泡が膨張する、七色の光を受けて。しんがりにふさわしい膨大なる演出)、どれも今パフォーマンスしても新鮮だと思う。半世紀余前に実現された!のです。何よりの財産は物ではなく創造力、 gutai の資料はその肥やしになるでしょう。願わくは膨大な資料が活かされること、そして新美術館がピナコテカになることを願いつつ。

造形の純粋性を求める吉原治良は作品にタイトルを付けることを嫌っていました。白髪さんはそれにに渋々従って<無題>とか<作品 B>とか無機質なタイトルを付けていました。しかし白髪さんにとってはタイトルは必然性があるのです。とりわけ ‘59年から始まった<水滸伝シリーズ>は白髪一雄の画業の核になるものですが、それは中学生の頃から原書まで読むほど傾倒していて白髪さんのの血肉になっているものです。ですから、作品は登場人物の表現なのです。

Seeking purity of art, Jiro Yoshihara disliked the practice of giving titles to works. Kazuo Shiraga followed Yoshihara’s lead somewhat grudgingly, using lifeless, unemotional titles such as Untitled and Work B. But Shiraga actually saw a title as essential. This is particularly clear in the SUIKODEN series of paintings that he began in 1959, which forms the core of his oeuvre. The series is based on the Water Margin stories that had become an inseparable part of Shiraga’s makeup. He even read them in the original Chinese while still in junior high school. The works in this series are representations of SUIKODEN characters.

確か亡くなられる前年、アート・遊の展覧会で<地耗星白日鼠(Chizokusei Hakujitsuso) >をご覧になった時、〜<地賊星鼓上蚤(Chikousei Kojoso)>とこの2点がなかなかかけへんかったんや、なんでぃゆうたらこの二人はこそ泥とチンピラやからわし嫌いなんや!ほんでどうしてもかけぇへんかったんや、これでようよう水滸伝が完結したのや〜と感無量でおっしゃっていたお顔が今も目に浮かんできます。

The year before he died, he saw Chikousei Hakujitsuso at Art U’s exhibition. I remember vividly the depth of emotion in his face as he talked about this work and Chizokusei Kojoso: “Those two were particularly difficult because I hate the characters; one’s a sneak thief, and the other’s a hoodlum. I couldn’t paint them for ages, so they ended up being the last in the series.”

成る程108点のシリーズの内、約 106点が ‘60年代に制作されている、それは比叡山修行前の最も油の乗った壮年期でありまた生白髪(なましらが)の時期です。それらの作品のクオリティの高さと点数からいっても白髪の画業にとり水滸伝は抜き差しならぬものであることは申すまでもないと思います。そして何よりも私の探究心が刺激されるのは、白髪一雄を形成する大陸・中国文化の周波数の根源です。それは日本文化のルーツへの憧憬でもありましょう。

That explained why of the 108 works in the series, 106 were created in the 1960s, the “unadulterated Shiraga” period when the artist was in his prime, before going off to Mount Hiei and becoming a monk. In terms of both quality and number of items produced, the SUIKODEN series is indisputably an inextricable part of his work. And what stimulated my curiosity more than anything was that its origin was on the same frequency as the continental-Asian, Chinese culture that had a formative influence on Kazuo Shiraga. His attraction to the roots of Japanese culture surely comes from the same source.

白髪の一番のお気に入りは京都国立近代美術館蔵の< 天魁星呼保義(Tenkaisei Kohogi)>です。天暴星両頭蛇は猟師だったので、狩猟好きの白髪が最も共鳴した人物であったのではないでしょうか 。梁山泊ではないが<水滸伝シリーズ>が一堂に集結する展覧会があったらと夢は膨らみます。国内の美術館に 40 点 余収蔵されていますから夢のまた夢ではないでしょう。はたまた海外に流出した水滸伝シリーズを訪ねてお遍路の旅をしょうかな?と私の妄想は膨らんでいくのです。

Shiraga’s personal favorite is Tenbousei Ryoutouda, which is in the collection of the National Museum of Modern Art, Kyoto. The Tenbousei Ryoutouda character was a hunter, which is almost certainly why he resonated most with Shiraga, who was himself a keen hunter. Osaka may not be Mount Liang, but I have growing dreams of an exhibition that brings together all the characters of the SUIKODEN series. Japanese art museums already have more than 4o of the works in the series, so maybe the dream is not totally unrealistic. Perhaps I could start with a pilgrimage to visit all the SUIKODEN works that are scattered around the world? This dream is getting more and more interesting!

追; #177「聖狗」はもともと無題でありましたがアート・遊の展覧会の時に自らマジックペンでキャンバスの裏にタイトルを記されました。その様はまるで名無しの子供にやっと名前を付けられたという産みの親のお顔でした。

PS: Work #177, Seiku, started out without a name, but when Kazuo Shiraga re-encountered it at the Art U exhibition, he wrote the title on the back of the canvas with a permanent marker. He looked as delighted as a parent separated from a child at birth who was finally able to give the child its name.

古来日本文化には~遊びをせんとや生れけむ、戯れせんとや生れけん、遊ぶ子供の声きけば、我が身さえこそ動がるれ~梁塵秘抄(りょうじんひしょう)や禅語「遊心」が風流=芸術の根底にあります。

西洋ではホイジンガの「ホモ・ルーデンス」という遊戯が人間活動の本質であり、文化を生み出す根源だと思想があります。

私には三人の赤ん坊を育てた臨床体験が鮮明に脳裏に刻みこまれています。乳に満ち足り、寝足りた赤ん坊の行為ですがそれはそれは好奇心に溢れています。手足で遊んだり、触れるものは何でも口に持っていったり、触覚、視覚、聴覚をフル回転して一時の休みもなく遊んでいます。ハイハイができるようになるとその好奇心は一段と高まり、その好奇心により運動能力が発達していく様に見えます。

この好奇心こそ人間の本質であり asobiではないでしょうか?

さて前書きが長くなりましたが、その狙いは私の 密やかな asobiを正当化するための方便でもあるのです。

寛仁大度な作家さま方が私の“asobi”に目くじらたてられないことを願っての、

ところで、今私が目にしている作品はかってはあなたの胎内から産み出されたものですね。安産であったか、七転八倒の難産であったかはわかりませんが産み出された作品はもう一つの独立した人格?というか画格を持った生命体として存在しているのです。

そして見る者の心に生命の輝きを点火させ、時空を超えて生命のエネルギーを放出し続けるのです。

もうそれは産みの親である作家さんの圏外の事象なのです。

感動された時、もうその人のPersonal possessionになるのですから。

感動するとは一体どういうことでしょうか?

それは見者の内にある感性が呼び覚まされる、そして共鳴することではないでしょうか。見者の未窟の鉱脈を探り当てる歓喜と奏でる協奏曲こそ至宝の asobi ではないでしょうか?

References to play abound in Japanese culture passed down over the centuries. Good examples include one of the Ryojin-hisho* songs, “We are all born to play, born to have fun. When I hear the voices of children playing, my old body still responds, wanting to join in,” and the Zen word, Yushin/Asobi-gokoro (A playful mind/Playfulness). Such references indicate that play (asobi) is one of the foundations of art and the popular arts. Similar ideas can be seen in the West, such as Johan Huizinga’s Homo Ludens (or Playing Man), which discussed the importance of play as an essential element in human activity and the origin of culture.

The experience of nursing and rearing my three children is vividly imprinted on my mind. Babies who had plenty of breast milk and sufficient sleep were absolutely brimming with curiosity. They played constantly, with their senses of touch, sight, and hearing in high gear, playing with their hands and feet, and putting anything they touched in their mouths. Once they started crawling, their curiosity went up another gear, seeming to drive the development of their physical abilities and motor skills. This curiosity is surely the essence of humanity, the manifestation of Asobi-gokoro or playful mind.

Please forgive the lengthy introduction, which largely serves to justify my own furtive play. I hope my playing will not overtax the artists’ generosity and compassion. You know, the artwork that I am now looking at has come forth from your womb. I don’t know if it was an easy delivery or an excruciatingly painful, difficult delivery, but now that it is done, the work that you gave birth to exists as a separate entity with its own independent character and its own life.

That entity sparks the fire of life in the hearts of viewers, triggering the ongoing emission of life energy that will transcend time and space. What happens is already outside the control of the artist who gave birth to it. When your art moves someone emotionally, that experience becomes his or her personal possession.

What does it mean to move someone? Surely it means stirring the viewer’s emotions and resonating inside him or her.Performing a ‘concerto’ that resounds with the joy of discovering an untouched vein of something precious inside the viewer is surely the most treasured form of play.

*Ryojin-hisho (Songs to Make the Dust Dance on the Beams): a folk song collection compiled by Cloistered Emperor Go-Shirakawa in the end of Heian period. (12th century)