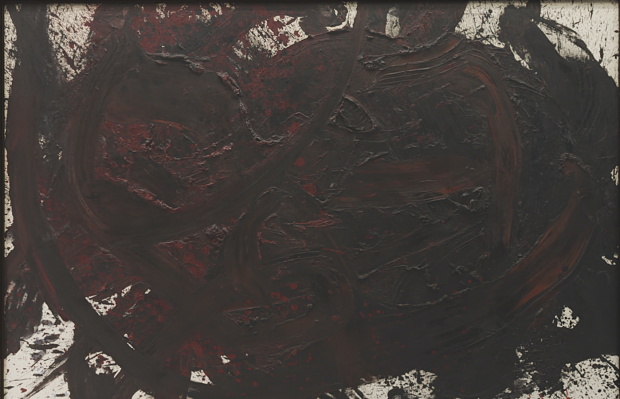

Kazuo SHIRAGA”The Water Margin Hero Series”天立星双鎗将 Tenritusei Kososho 1964

Wonted!

天立星双鎗将 Tenritusei Kososho 1964

序列15 Order15 薫平 Dong Ping

序列15位と高く、両手に槍を持って戦うのを得意とする。

風流双槍将と呼ばれ武芸だけではなく礼教・学問・管弦にも通じていた。

文武両道のキャラクターは白髪が好みでは。おそらく素晴らしい作品だと想像するばかり。片鱗の資料も残されていない。残念です。

It is as high as 15th place and is good at fighting with a spear in both hands.

He was familiar with not only martial arts but also courtesy, learning, and music.

I think this character is probably someone who likes Siraga, so I think it’s a wonderful work. No material is left. I’m sorry!